This piece is a stark reminder of the risks of doing business in China and the need to do thorough background checks on third parties and to increase fraud awareness among tout employees.

Nigel Layton Partner - Crisis & Disputes

Fraud & corruption in the pharmaceutical industry in China

Fraud & corruption in the pharmaceutical industry

In the sales and marketing divisions of many corporations the benefits of engaging in bribery often outweigh the risks of getting caught and so there is often a sub-culture and acceptance of engaging in such unethical activity to secure contracts or performance-related commissions.

In the pharmaceutical and life science industry in Asia the most common fraud and corruption schemes are:

- Sales teams bribing doctors

- Diversion of product

- Virtual speaker fee manipulation

- Fictitious sales and fake contracts

- Tendering fraud and bid-rigging

- Off label use and promotion of pharmaceuticals

- Counterfeit drugs and intellectual property rights infringement

The root causes for the above are many, but mainly driven by:

- Pressures placed on frontline sales teams to meet performance targets;

- Buyers of drugs and medical devices, usually doctors, expecting kickbacks in exchange for purchasing and prescribing products;

- Differences in the sales price and release dates of pharmaceutical products in different countries, e.g., between India and China; and

- Inadequate enforcement of Chinese commercial bribery laws, such as Article 8 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law (“AUCL”) and Article 163 of the PRC Criminal Law, Chinese legislation that specifically proscribes such malfeasance.

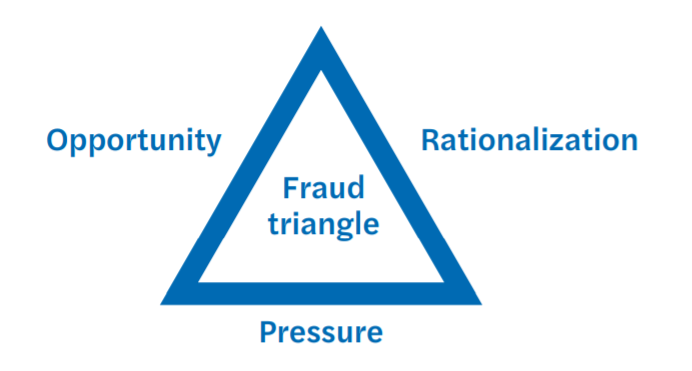

From a criminological perspective, the three elements of Donald R. Cressey’s fraud triangle that describe the prerequisites for the occurrence of fraud and corruption, i.e. pressure, opportunity, and rationalization, are all present and so in this perfect storm fraud and bribery becomes a norm, rather than an exception.

Type of fraud & corruption examples

Sales targets and performance incentives

Efforts by corporations to reduce fraud and corruption risks are constrained by ever-increasing compliance and investigation costs and by pressures to meet sales targets in an extremely competitive market.

By way of example, sales managers of Chinese healthcare industry companies often receive a commission of between 1% -5% on the sale of a drug, medical device or healthcare consumable, which is perfectly acceptable provided that the transaction is properly authorised and accurately recorded in the accounting books and records.

However, the same sales manager is often expected to pay a 1%-5% kickback to a doctor or hospital in order to secure a sale, which is not acceptable. It is unequivocally illegal by Chinese law, as indeed it is by law in most jurisdictions around the world.

Many sales and leases of medical equipment in China, even by large multinational companies, do not have written contracts detailing the terms and conditions, and if they do it is not uncommon for contracts to be altered or forged. Such deceptions often relate to the sale of healthcare products that have not actually occurred or are materially inaccurate.

Free consumables, which may be packaged up in the sale of an expensive medical device, may not reach the customer at all, but instead will be sold on the black market.

These fictitious and fraudulent sales not only allow employees to embezzle cash but help to fund bribery schemes.

Expense fraud

In the past, and to a lesser extent today, there was a huge underground industry in China producing fake invoices and other supporting documents. These slips of serial numbered paper, with a date of transaction, description of services or product, and value of transaction (called a “fa piao“ 发票 ) can now be checked fairly easily against a Chinese tax bureau hotline for legitimacy, and so a new underground industry has emerged that issues genuine invoices and supporting documentation, but for exaggerated or non-existent goods and services.

There are restaurants, hotels and conference organisers across many cities in China that earn income issuing receipts and invoices for meetings, events, seminars and forums that never happened, or inflate and overstate actual expenditure. Often a middleman called a “Huang Niu” (黄牛) will charge about 8% of the invoice value to source and provide seemingly genuine “fa piao”s.

The dishonest sales team members can claim reimbursement of expenses from their finance departments using these fake documents. Sometimes the money will be kept by the sales team members, but usually the funds will be used to bribe doctors and officials, often in the form of gift cards, stored value cards, online wallets (such as WeChat Pay and Alipay), junkets, electronic goods, jewellery, foreign real estate and even motor vehicles.

The United States Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

Foreign pharmaceutical and healthcare firms, especially from the US and Europe face greater risks manufacturing and selling their products in China. They have to comply with not only Chinese laws, drug approval processes, and other local regulations, but also “long-arm” legislation such as the FCPA and UK Bribery Act.

International pharmaceutical and medical devices products are often perceived in the Chinese market to be superior and safer, and so they can secure higher prices than Chinese products. Baby milk powder formula is a good example because historically a large proportion of locally made milk powder had been proved to be adulterated with unsafe protein enhancing chemicals, some of which caused the death of babies and infants in China.

Higher selling prices invariably means higher sales targets and so the pressure to bribe and the Renminbi value of the bribe is exacerbated, creating a vicious cycle in which more imaginative and deceitful fraud schemes need to be employed to raise funds to pay higher value bribes.

If these schemes are employed by the sales team of a pharmaceutical company that is subject to the US FCPA and the doctor being bribed can be construed to be a government official (as many doctors in the People’s Republic of China can be argued to be) then the company and its directors are exposed to huge risks.

Speaker fee bribery

In the pharmaceutical industry in Asia, it is common for sales and marketing teams to invite medical doctors to speak at round table discussions, seminars and small medical meetings and promote their products. Like the expenses fraud above, meetings at locations such as restaurants and hotels, or products bought from supermarkets and stores to be consumed at such meetings, can be fabricated or exaggerated with the submission of fake invoices, thus deceiving managers and circumventing the companies’ approval processes.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic these medical promotion events have gone online, creating an opportunity for unethical sales teams to pay bribes to doctors directly, in the form a speaker fee, to prescribe their products.

Doctors’ speaker fees can vary from RMB1,000 to 3,000 (US$155 – 465) depending upon the grade and influence of the doctor, e.g., municipal, regional or national level.

To secure preapproval for doctors’ speaker events the sales teams usually need to submit a proposal to the company’s finance, compliance and management departments detailing nature of meeting, date, costs, speakers, and number of attendees. A common fraud scheme is to fabricate the identity of registered attendees, or makeup numbers with fabricated online identities, and secure the funding for the fictious event.

Tendering fraud

Another common fraud scheme is for the sales team of, say, Company A (or through a tendering agent) to prepare bidding documents for their own company, but at the same time prepare the tender documents for “competing” Companies B and C.

This is done with full knowledge and acquiescence of all parties, and letterheads, seals and company shops are shared between the conspirators, with each taking it in turn to submit the purportedly lowest bid and win the contract.

To keep out competition, the sales teams will collectively engage in underhand methods to place pressure on other companies, either to join their cartel, or force such competitors to be excluded from tendering fairly in the future. They do this by exploiting connections (“guanxi” 關係) with corrupt government officials who can intimidate and make life difficult for anyone who seeks to disrupt these arrangements, either by colluding with tendering agents, or by exploiting bureaucratic red tape.

Product diversion

As evidenced during the Covid-19 Pandemic, newly developed drugs and vaccines are often approved by respective countries’ Food & Drug Administrations and Health Authorities and released into the market at different times and with vastly differing pricing. This creates on opportunity for imaginative and unethical sales teams and third-party distributors to divert product and make profits.

For example, newly released drugs can be approved and prescribed locally in a country such as India before they became available in China. When the same drug eventually does become available in China, albeit branded under a different name, the price can be considerably higher. Proof of this risk is supported by anecdotal evidence when China restricted import and export of goods during the pandemic in 2020/21. During this restriction the sales of drugs intended only for the Indian market went down by 50-70%, inferring that the scale of illegal diversion of pharmaceutical products from India to China was huge.

Medical tourism, again very common in Asia due to the differing costs and availability of healthcare from country to country, also exacerbates diversion of product. Once a particular course of medicine is prescribed to a patient in India or Thailand, for example, the patient will often need to continue the course of treatment when they return to China and turn to unauthorised supply and distribution channels.

Off label use and promotion of pharmaceuticals

Off label use means that a drug is used for non-approved indication, i.e. for the prevention, treatment or cure of an illness or ailment for which it is not intended or authorised.

The incentive to a sales team is simple – to increase sales, meet targets and secure a sales commission or bonus. This will be contrary to the pharmaceutical company’s corporate responsibility guidelines and expose it to serious legal, regulatory, financial, reputation and ethical risks.

Counterfeit drugs and intellectual property infringement

It is not inaccurate, nor indeed unfair, to say that China is the largest source of pirated and counterfeit products in the world. Whilst a fake handbag or wristwatch may well contravene trademarks, copyrights, patents, and many local and international laws, it is not going to kill or harm you.

Like fake chemicals, aircraft and automobile parts, food, and electrical goods, counterfeit pharmaceutical products could harm or kill and so these are subject to strict regulatory and legal scrutiny.

As with fraud and bribery, pharmaceutical companies have a corporate responsibility and legal duty to minimise risk of harm to society and prevent counterfeit drugs and products entering the market.

Challenges & risks

Fraud and bribery schemes can go undetected for years, if ever. Often the employees of pharmaceutical firms in China believe that they do not need to comply with the FCPA or the UK Bribery Act. Many also believe that the chances of getting caught by Chinese economic police or graft busters for bribery and corruption is very small as so many people do it and think it is the norm for doing business in China.

A company’s internal audit or compliance department may not have the technical capabilities or forensic expertise required for fraud detection and the minimalization of integrity risks, such as investigative interviewing, digital forensics, and data analytics technology for fraud detection.

Compliance and internal audit teams may rely solely on sampling techniques and outdated risk assessments and internal audit work plans that may fail to identify red flags, and thus allow the most damaging bribery schemes and fraudulent activity to go under the radar.

Third parties, such as distributors, tendering agents, vendors, and logistics suppliers may collude with dishonest sales teams and unethical management, thus escaping detection and scrutiny. These third parties may have non arm’s length relationships and undisclosed connections with government officials.

If a company fails to employ pre-employment screening and investigative due diligence on these third parties, the risks of fraud and corruption can quickly escalate. Whilst whistleblowing and ethical reporting hotlines have become more prevalent in pharmaceutical firms in China, especially within the large established multinational firms, these hotlines are often abused by employees and competitors who can make vindictive or spurious allegations, resulting in internal investigation and compliance teams wasting finite resources and time following false leads and lines of inquiry.

Another challenge is that it is common practice for senior sales managers throughout the healthcare industry to train up the “new recruits” in how to set up fake meetings, obtain fake supporting documentation, draft fake contracts, bribe doctors and other buyers of drugs, medical devices and consumables, create fictious online identities, communicate using encrypted online messaging platforms, and of course cover their tracks.

Often, the sales employee, particularly in the less experienced frontline sales teams, will resign as soon as they get a hint that an internal investigation is underway. Some sale team members cooperate with internal investigations, and some do not, but very rarely will detected bribery cases be handed over to Chinese law enforcement agencies for prosecution through the criminal or administrative courts.

Corrupt sales personnel, whether they resigned or were dismissed, will often join a competitor pharmaceutical firm. As pre-employment screening and background due diligence is rarely performed on junior staff in China the new employer will inadvertently inherit a more streetwise and corrupt employee who is well versed in the art and concealment of bribery.

As a deterrent and a demonstration of zero tolerance of fraud and corruption, an ethical and responsible organisation should prosecute corrupt employees in the criminal courts. However most executives and senior management prefer a quiet dismissal, rather than risk being exposed to the full glare of a public prosecution and having their good name exposed in legal proceedings.

Finally, finding talented people in China is as challenging as anywhere in the world, if not more so. Too often greater value is placed on finding people with experience and the ability to sell products, than on hiring staff with qualities such as integrity and honesty.

Our services offerings

At Mazars we have dedicated forensics and investigation teams throughout Asia, with offices in most cities across greater China. We can help pharmaceutical companies and their legal advisors with:

- Fraud & corruption investigations

- Investigative due diligence (on-site inquiries and public domain research using artificial intelligence-powered technology)

- Forensic accounting and fraud audits

- US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act & UK Bribery Act risk assessments

- Data analytics for fraud and bribery detection

- PRC Data Security Law & Personal Information Protection Law compliance risk assessments and audits

- Background screening and inquiries

- Intellectual property rights investigations and risk assessments

- “Hands-on” forensic and investigation project management

Get in touch

If you would like to contact our team, please do not hesitate to use the link below: